My favorite books of 2019

#

Last year it took me 11 months to write up my favorite books and now it seems I’m making a tradition of it.

White Kids: Growing Up with Privilege in a Racially Divided America, Margaret A. Hagerman

This was the most challenging and thought-provoking book I read last year. Hagerman looks at the school choices of upper-middle class white parents in a small Midwestern city (The location is anonymized, but based on the described geography, my guess is Madison, Wisconsin. It was fun to try to figure that out while reading.). The parents fall into three groups: those that live in a conservative exurb and deny racism is a problem, those who live in a neighborhood with a majority-white “good” school, and those who desire diversity and send their children to an integrated school. While the parents had differing attitudes towards race, all of them are well-off, and therefore are able to choose where their kids go to school and what activities they do. Hagerman investigates how these “bundled choices” affect the attitudes about race among the kids.

One of the difficult things about this book is that the author does not provide any guideposts for right action. Even the parents at the integrated school are criticized for supplementing their kids’ education with extracurricular activities:

Even with these priorities of working to confront inequality, Tom and Janet Lacey at times unintentionally reproduce the very inequality they seek to disrupt. For instance, they supplement their daughter’s education by providing Charlotte with a number of additional extracurricular learning opportunities such as tutoring, private music lessons, summer programs, and elaborate trips and vacations, among others. They provide Charlotte with a private opportunities not available to other students, a reality that at times contradicts their stated intention of supporting equal public educational opportunities for all. Tom and Janet, along with other affluent, white parents in this study who identify as progressives, are often faced with what I refer to as a conundrum of privilege: how much work is enough?

There’s no way to avoid passing on the advantages of wealth and whiteness. In her conclusion, Hagerman writes that she can offer no easy answers:

[P]arents of race- and class-privileged children are faced with a difficult paradox: in order to be a “good parent,” they must provide their children as many opportunities and advantages as possible; in order to be a “good citizen,” they must resist evoking structural privileges in ways that disadvantage others. Decisions about navigating this paradox are part of a complex, ongoing, everyday process of parenting, a process that is filled with many other challenges, day-to-day trials, and unintentional missteps. This is not easy work, and it also may never be possible to solve structural problems entirely through individual acts.

Her hope is that rich white parents stop hoarding as many resources as possible for their own children, and “accept the radical notion that the happiness, success, health, and well-being of other children is as important as that of their own.”

This seems difficult to implement in America’s increasingly unequal society. I doubt structural racism can be solved by individual action, though understanding how it affects our society is clearly important to making any changes at all! Perhaps by making our society more equal and less zero sum, we can raise up all children. Given our history, however, a relative decrease in inequality could be regarded as a threat for those who already have privilege (see Strangers in Their Own Land from my 2017 books).

How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them, Jason Stanley

This terrifying book should be titled How Fascism Works a Little Too Well. It’s a playbook for authoritarianism, and contrary to “it can’t happen here” sentiments, it shows how fascism subverts the principles of democracy to take control. Most fascist governments were elected.

The Decline and Fall of the British Empire: 1781-1997 by Piers Brendon and Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe by Peter Heather

I read two histories about the fall of empire. The first is a biting account of the accidental expansion and ultimate failure of the British empire. It’s full of amusing tidbits about the oddities of the imperialists, like the general who held interviews while lying naked in bed and combing his body hair with a toothbrush. The British claimed liberal principles but their lack of follow-through provided a lever for criticizing the Empire’s policies at home and in the subject territories. Brendon argues this hypocrisy was a fatal flaw.

Despite controlling a quarter of the globe, the British empire was a paper tiger, hollowed out and weak. When the Japanese easily defeated them, nationalists everywhere saw their chance and took it.

The second is about how Rome managed its relationships with border states. I picked up Empires and Barbarians because we took a trip to Barcelona (Remember trips? Those were fun.). I wondered, why did the Visigoths come here and how did they get here and take control? Empires and Barbarians answers that question, but it is about the broader question of how Rome stimulated the political development of peoples outside the frontiers.

Rome did not set up thousands of miles of wall and guard it. There were border outposts, but they mostly served to manage trade back and forth across the border. Barbarian states were essential for providing supplies to troops on the border, and they fought wars with each other in order to become Roman client states. Needing to dominate other groups as well as stand against the Empire’s superior forces led to political development.

Even without the Huns, moreover, these processes of development would eventually have undermined the Roman Empire. Looked at in the round, what emerges from the first-millennium evidence is that living next to a militarily more powerful and economically more developed intrusive imperial neighbour promotes a series of changes in the societies of the periphery, whose cumulative effect is precisely to generate new structures better able to fend off the more unpleasant aspects of imperial aggression. In the first millennium, this happened on two separate occasions. We see it in the emergence of Germanic client states of the Roman Empire in the fourth century, and again – this time to more impressive effect – in the rise of the new Slavic states of the ninth and tenth. This repeated pattern, I would argue, is not accidental, and provides one fundamental reason why empires, unlike diamonds, do not last forever. The way that empires tend to behave, the mixture of economic opportunity and intrusive power that is inherent in their nature, prompts responses from those affected which in the long run undermine their capacity to maintain the initial power advantage that originally made them imperial. Not all empires suffer the equivalent of Rome’s Hunnic accident and fall so swiftly to destruction. In the course of human history, many more have surely been picked apart slowly from the edges as peripheral dynasts turned predator once their own power increased. One answer to the transitory nature of imperial rule, in short, is that there a Newtonian third law of imperial rule. The exercise of imperial power generates an opposite and equal reaction among those affected by it, until they reorganize themselves to blunt the imperial edge. Whether you find that comforting or frightening, I guess, will depend on whether you live in an imperial or peripheral society, and what stage of the dance has currently been reached.

The two tied together for me. One of the themes of Empires and Barbarians is that empire is sustained by a technological gradient. The Empire maintains hegemony because it is more economically efficient. As technology diffuses, border states become more powerful. The empire is still more powerful than individual competitor states, so they may be contained one at a time and played against each other (reminiscent of the British “divide and rule” strategy), but simultaneous crises can be fatal. As the empire loses land, it loses economic power, setting off a cycle of decline.

The lessons for today’s leaders are there, but so is the historical fact that wicked problems usually don’t get solved.

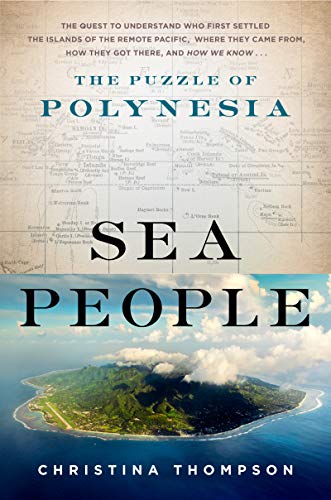

Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia, Christina Thompson

I highly recommend this book if you are interested in Polynesia. How did the Polynesians settle the islands of the Pacific? Where did they come from? Why did they stop voyaging? Thompson frames these questions through those who have asked them: from the first European eye witnesses, to early anthropologists and on to modern scientists and Polynesians rediscovering and reinventing their culture. This is a fascinating book about one of the greatest achievements of humanity.

My full list of books from 2019 is below. You can also review lists from previous years: 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 (retroactive favorites), 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018.

White Kids: Growing Up with Privilege in a Racial Divided America, Margaret A. Hagerman

Foundryside, Robert Jackson Bennett

The Buried Giant, Kazuo Ishiguro

Burning Paradise, Robert Charles Wilson

The Guest Cat, Takashi Hiraide (translated by Eric Selland)

Binti, Nnedi Okorafor

Ninefox Gambit, Yoon Ha Lee

Raven Stratagem, Yoon Ha Lee

Revenant Gun, Yoon Ha Lee

The Retreat of Western Liberalism, Edward Luce

The Dispatcher, John Scalzi

Fox 8, George Saunders

For All the Tea in China: How England Stole the World’s Favorite Drink and Changed History, Sarah Rose

Small Animals: Parenthood in the Age of Fear, Kim Brooks

The Decline and Fall of the British Empire: 1781-1997, Piers Brendon

Where Angels Fear to Tread, E. M. Forster

Cinderella Ate My Daughter: Dispatches from the Front Lines of the New Girlie-Girl Culture, Peggy Orenstein

Tattoo, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán (translated by Nick Caistor)

How Do We Look: The Body, the Divine, and the Question of Civilization, Mary Beard

Life is sho, Enric Jardí

Elysium Fire, Alastair Reynolds

Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life, William Deresiewicz

Slow Bullets, Alastair Reynolds

How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them, Jason Stanley

Your Four-Year-Old: Wild and Wonderful, Louise Boutes Ames and Frances L. Ilg

Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth, Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos H. Papadimitriou, art by Alecos Papadatos and Annie Di Donna

Maurice E. M. Forster

Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe, Peter Heather

The Compleat Traveller in Black, John Brunner

Sea People: The Puzzle of Polynesia, Christina Thompson

A Wizard of Earthsea, Ursula K. Le Guin